I've recently been challenged by a reader to provide a more concise statement of my fundamental disagreement with Gangadean. It's a bit tricky to do so because the disagreements are textured and often subtle which requires some detail. But I think it's worthwhile to give up on some precision to make something more accessible and bite-sized.

If I had to boil down my main disagreement with Gangadean I would have to say that it's a disagreement about 1) the need for, and 2) the inevitability of clarity.

Gangadean's entire worldview hinges on two fundamental claims.

1) That there is clarity at the basic level. Gangadean thinks that it's impossible for some subset of his beliefs to be mistaken or false. That is to say, for a significant portion of his beliefs about reality, it's in the strongest sense impossible for him to be wrong. For instance, he believes the laws of thought are universal and exceptionless. He believes that God exists. He believes that the bible is the word of God. He believes that humans are rational animals. He believes matter is not eternal. He believes that good for humans is to gain knowledge of basic things. He believes that evil for humans stems from failing to know what is clear. He believes that free will is compatible with divine foreknowledge and predestination. He believes that knowledge = maximally justified true beliefs. He believes that the self exists. He believes that the self is not eternal. He believes that reality is composed entirely of either matter or spirit. There are lots and lots of others, but you get the drift. It all supposedly starts from the laws of thought (e.g. 'a is a') and via deduction (or "good and necessary consequences") gets you to an airtight, knock-down, argument for each of the propositions just enumerated (and more!).

2) That, in some sense, we need this kind of clarity. Without clarity at the basic level, without this kind of indubitable certainty of basic things, we're in really bad shape. Worst of all, skepticism (i.e., we can't have any knowledge) follows. But also, nihilism (life has no meaning) follows. Further, without this kind of clarity, there's no point in arguing, or talking---absurdity and contradictions follow.

For Gangadean, the two are related. He uses 2) to support 1). That is, he asks his objector to consider what the world would be like if there was not clarity at the basic level (this is part of Gangadean's "transcendental method"). Would there be any knowledge? Would there be meaning? Would there be any point to talking? Arguing? Could we even have thoughts? If not, then the things enumerated in 1) must be clear to reason.

Where I fundamentally disagree:

I fault Gangadean for failing to make an indubitable case for 2) which in turn undermines his reasons for accepting 1). In other words, he tries to argue for 1) by appealing to 2), but fails to establish 2) and thus fails to establish 1).

To date, I have yet to hear a watertight case from team Gangadean establishing the need for clarity (i.e., thesis 2)). I think that our world could very well be a world in which we can't have that kind of certainty about anything. But importantly, I don't see how nihilism, skepticism, or contradiction follows from this fact. This is where Gangadean seems to make elementary errors in reasoning--by helping himself to unproven assumptions and ultimately begging the question.

Let's take the issue of skepticism since I think that's supposed to be the main boogey-man. In its extreme form skepticism is the thesis that knowledge is impossible for anyone to ever attain about anything. Gangadean claims that without clarity at the basic level, this extreme form of skepticism follows. Further, it would be a contradiction for one to affirm this skepticism, since in doing so, you're claiming to know something (namely that we can't know anything) while denying the possibility of knowledge, something must be wrong. So skepticism must definitely not be true, in which case there must be clarity at the basic level.

The problem with this approach is that Gangadean is already assuming that knowledge is connected to clarity in a way that helps his ultimate agenda. That is, in order to establish the need for clarity, he's helping himself to a particular conception of the nature of knowledge, which requires clarity. But just why should we think that knowledge requires clarity in the first place? Where's that argument? I hope you can see where this is going. If it turns out that we can have knowledge without clarity, then skepticism simply doesn't follow from a lack of clarity. So Gangadean must show that we cannot possibly have knowledge without clarity at the basic level--and to date, he hasn't done so. He merely assumes as much. [Note the above reasoning is also mistaken because one can affirm skepticism without claiming to know that skepticism is true because affirming isn't equivalent to knowing.]

The same is true of the charge of nihilism. Just why or how does nihilism (meaninglessness) follow from the lack of clarity/certainty at the basic level? This again isn't a thing argued for--it's taken as obvious by Gangadean. Of course, if Gangadean is allowed to define 'nihilism' however he pleases, then the point will be trivial. But we needn't allow that. Or if Gangadean is permitted to stipulate his favored concept of nihilism or meaninglessness, then again the point could be trivial---but we needn't allow that. Gangadean needs to present his case for his favored concept or definition of meaninglessness in the pertinent sense and then explain how it logically follows from the lack of clarity. That's a tall order. Relatedly, why should talk be pointless? Why should arguing be pointless if it's possible for us to be wrong about everything?

Finally, Gangadean's case for 2) ultimately fails because it depends on a bad conflation. Gangadean and his followers are prone to conflate possibility with actuality. To deny the clarity thesis consits in merely allowing that it's possible for all of us to be wrong about even our most basic beliefs. [Recall how Gangadean defines clarity: "for p to be clear to S is for it to be impossible that S is wrong about p"]. Importantly, that's not the same as claiming that we are in fact wrong about the most basic things. The former is about what's possible and the latter, what is actual. To say that it's possible that I could be wrong that God exists, or that 'a is a' is not to say that my belief in those propositions is actually wrong. And if by challenging the clarity thesis I am not saying I am actually wrong about my belief in 'a is a', then none of the other doomsday predictions that Gangadean makes, follows from the denial of the clarity thesis. [Again you have to pay close attention to just what the clarity thesis is--to say P is clear for you, is to say that it's impossible for you to be wrong about P].

It's perfectly consistent for me to believe that God exists while in the same breathe believing that it's at least possible for me to be wrong. Just as it perfectly consistent for me to believe that it will rain tomorrow, while believing that I could be wrong. Even more, in either case, I can rationally remain confident in each proposition provided my reasons provide ample support even if the reasons aren't conclusive. And my beliefs can be correct and the basis of rational decision making. Indeed even in a situation where it's possible for me to be wrong about my belief that God exists, I can know that God exists. Thus, skepticism doesn't follow from denying clarity. Neither does nihilism follow. Thinking continues to happen. Talk and inquiry continues to have a point. Conversations need not end. It's not the end of the world. We don't need clarity not even at the basic level. We can have knowledge without clarity, we can have meaning without clarity--we can fail to have our cake and fail to eat it too.

A critical examination of the basic beliefs of Surrendra Gangadean, Owen Anderson and Westminster Fellowship Phoenix, AZ.

Monday, November 6, 2017

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

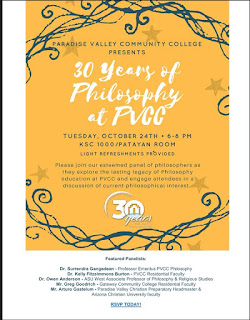

Gangadean Event at PVCC

A reader made me aware of an upcoming (tonight) event which features Gangadeanian speakers. It's open to the public and is supposed to feature discussions as well so it might be a good place to raise some of your critical objections! RSVP here.

Also, if any of you would like to attend and report back to me your experience, I'd be happy to feature it in this blog.

Also, if any of you would like to attend and report back to me your experience, I'd be happy to feature it in this blog.

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

FAQ link fixed.

Apparently my link to the FAQ page was down. Sorry for anyone that was trying to access it via the above links. It's fixed now. Cheers.

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

Response to a Comment (edited)

There was a comment to my latest post and as I started to respond I noticed that it should merit a separate post. My thanks to the commenter. Here's what they wrote:

Gangadean cares about G-knowability because his apologetic goal is to demonstrate God's existence in a way that is consistent with Historic Christianity and Romans 1:19-20. Without "clarity" Romans 1 fails to be true, and the eternal punishment for unbelief is unjustified. The basic things being known in the E-knowable sense doesn't meet this burden of proof.

Does it follow that if basic things are E-knowable, they are not transcendentally necessary? Why think that if reason "as the laws of thought" is E-knowable, it cannot also be G-knowable? Wouldn't everything that is G-knowable also be justified according to lower evidential standards as well?

My response:

As the other responder noted below, there's debate about just what counts as "historic Christianity" in the relevant sense--just as there is room for debate about what the text you cited says. In other words, the Gangadeanian needs to argue for, rather than presuppose, that their notion of historic Christianity and their reading of Romans 1:20 is the correct one.

Here's another way to make the same point with a bit more detail. The word 'clarity' and its cognates (e.g., clear) are context sensitive terms. That is to say, what the term means differs depending on facts about the context of utterance. Linguistic evidence of this comes in various forms, but here's one bit. Context-sensitive adjectives admit to being modified by adding words like 'enough' which can then be followed by something of the form, 'for an X' where 'X' can denote a class, or even a purpose or function. For instance, 'tall' and 'far' are paradigmatic examples of context sensitive terms and it makes sense to say things like 'S is tall *enough to be a good center' or 'my job is far *enough to justify purchasing a bike.' We can also say things like, 'the water is clear *enough to swim in' or 'the diamond is clear enough to impress my soon to be fiance.' In fact, by adding 'enough' all we're really doing is making explicit the modifier that is often present, tacitly. The point is, rather than there being just one meaning to such predicates like 'clear' there are many depending on the context.

So what 'clear' or 'clarity' mean both with respect to historic Christianity and what Paul meant in Romans 1:20 needs to be understood against various contexts. Gangadean contends that it means something like "maximally provable" or "cannot be (rationally) doubted." One way to motivate such a view would be against the background of eternal punishment as you suggest: that is, when you ask about whether God's existence is clear, you're really asking whether it is clear *enough to make unbelief justifiably punishable by eternal damnation.

Here are some reactions to this:

1) Why think this requires Gangadean's notion of clear as "can't (rationally) be doubted?" In other words, I'm asking for an argument for Anderson's line, "maximal consequences entails maximal clarity." He never gives an argument for it, but treats it like a platitude. In other words, suppose as you suggest that God is justified in damming people for all eternity for failing to be in a particular mental state regarding his nature. What about this suggest to you that his existence should be clear in just the way that Gangadean provides? If you just find it obvious, then you're banking on an intuition that I honestly don't share. In fact, it gets worse. As I've pointed out before, even if God's existence were clear in the Gangadeanian sense, this isn't sufficient to make God justified in damming the unbeliever insofar as one also accepts the Calvinist doctrine that the unbeliever simply can't believe without having God change them in some fundamental way. And Gangadeanians are Calvinists in the pertinent sense. In other words, Gangadean wants to motivate his theory of knowledge (as G-knowledge) so that it's fair that unbelievers end up in ever-increasing spiritual death. But his Calvinism commits him to the view that the unbeliever can't possibly know what is clear without God changing their hearts (giving them Grace). What the clarity thesis attempts to provide the Calvinist doctrine takes away as previously noted here.

2) How do we know that even G-knowing something actually exemplifies achieving maximal clarity in the relevant sense anyway? For instance, Gangadean's theory of knowledge says nothing about the distinction between synchronic and diachronic belief-states. It is one thing to G-know a proposition at an instant of time, and quite another to G-know it over a span of time. Supposing that maximal consequences entails maximal clarity it's possible that maximal clarity actually demands more than Gangadean's conception does. For instance, maybe we should posit a theory of F-knowledge--where it's the sort of knowledge that stably spans over a significant period of time. Lest, you respond that it's simply not possible for humans to achieve this kind of knowledge, I would ask you for proof that isn't merely a generalization from your own experiences and observations. Interestingly, if we were to go this route I would think that there will be some subject-relativity since I would imagine different people have different abilities as it regards "hanging onto a belief" over a span of time. My point of course is not to motivate such a theory, but to suggest that by relying on the same assumptions to which Gangadean appeals in motivating G-knowability, we can proliferate at least another higher standard of knowledge. That seems like a bad result and thus a reductio against the general move Gangadean is making.

*3) Here's what I think is a particularly devastating problem. It's actually question-begging to cite theses from a particular reading of "historic Christianity" and a "proof text from the bible" as informing one's theory of knowledge in the current dialectic. That's getting things in reverse. It certainly isn't getting to G-know basic things from reason alone because in making such a move Gangadean is already assuming that there is such a thing as special revelation.

In other words, here are the terms of the debate as I understand them. Gangadean offers a theory of knowledge from "reason alone." I challenge the conclusion that it's the correct theory. Gangadean appeals to Christian doctrines and bible passages which he thinks his theory of knowledge makes the best sense of (purportedly adding abductive support of this theory as the correct one). That's viciously circular. We haven't yet settled that Christian soteriology is true, or that the bible (in any part) is true or the word of God---that's further down the line! We're at the more fundamental issue of what it means to know something so it's question begging to appeal to christian doctrine or "proof texts" to motivate your theory of knowledge. I've noted this here before.

In other words, here are the terms of the debate as I understand them. Gangadean offers a theory of knowledge from "reason alone." I challenge the conclusion that it's the correct theory. Gangadean appeals to Christian doctrines and bible passages which he thinks his theory of knowledge makes the best sense of (purportedly adding abductive support of this theory as the correct one). That's viciously circular. We haven't yet settled that Christian soteriology is true, or that the bible (in any part) is true or the word of God---that's further down the line! We're at the more fundamental issue of what it means to know something so it's question begging to appeal to christian doctrine or "proof texts" to motivate your theory of knowledge. I've noted this here before.

4) If Gangadean's theory of knowledge (or even the two-kinds of knowledge view) is being motivated by the worry that it would be unjust for God to create the universe in such a way that nonbelievers are eternally damned, then that still doesn't entail he's right. As I've mentioned earlier, maybe Gangadean's proposal about the eternal damnation of nonbelievers is wrong itself. For instance, a universalist about salvation would see no tension between the lack of G-clarity regarding God's existence and the purported "maximal consequences"---because they believe that no one will actually face those maximal consequences. That is, they could agree (not that they should) with Gangadean that maximal consequences entails maximal clarity, but then deny maximal clarity (in the Gangadeanian sense) because they believe (for independent reasons) that what Jesus did on the cross was so efficacious that it will ultimately save all i.e., that no one will be left in unbelief.

On to the second part of the commenter's response--they wrote:

Does it follow that if basic things are E-knowable, they are not transcendentally necessary? Why think that if reason "as the laws of thought" is E-knowable, it cannot also be G-knowable? Wouldn't everything that is G-knowable also be justified according to lower evidential standards as well?

I think there's some confusion in this comment. G-knowing something marks a higher epistemic standard than E-knowing that same thing. If there is an entailment at all, it's only going to be in one direction namely, "If S G-knows that p, then S E-knows that p" which is contrary to what is suggested at the beginning of this comment.

In fact, I don't know whether all that differs between the proposed two different kinds of knowledge are epistemic standards, so the above stated entailment might not even hold. For instance, they might be significantly different states--or belief-states that arise in significantly different ways--I have no clue---that would be for the Gangadeanian who wants to make use of this move to specify.

The last sentence seems to cut in the other direction. It's suggesting the entailment I just mentioned. Again, I don't know how the two purported kinds are supposed to relate to one another--that's for the Gangadeanian to flesh out. But it's far from obvious that the set of all G-knowable propositions contains the set of all E-knowable ones.

Sunday, August 13, 2017

Two Kinds of Knowledge?

A recurrent theme of my posts is that on Gangadean's theory of knowledge we know next to nothing. I take that as a reductio against his theory of knowledge because I take it that we know lots of things. Among the things which Gangdean's theory of knowledge invariable should make one skeptical about are propositions like, "the bible is the word of God" or "the bible is divinely inspired." The reason that this is the case is that Gangadean's standards for knowledge are impossibly high--we just can't seem to prove that the bible is the word of God. We might have various reasons to believe that it is so, but they fall short of proof. I would think that such a result is particularly troubling for the Christian that is moved by Gangadeanian epistemology. That is to say, a Christian wanting to maintain Gangadean's theory of knowledge (where knowledge requires certainty) ought to find it especially worrisome that such a theory entails that knowledge that the bible is really the word of God is impossible to attain. After all, Christians hold dearly to the scripture in guiding their lives--and the assumption that it contains divine truths is largely why this is so.

One way to resist this result is to simply say that we don't need to know things of the sort--maybe it's not important to know that the bible is special revelation. Perhaps it's enough to have a reasonable belief that it is so. But I doubt that any Gangadeanian would find that acceptable.

Another option would be to deny that Gangadean's theory actually leads to skepticism of the sort I've argued for. This is usually how Gangadeanians respond, but it's proven difficult for them-- Gangadeanian's are in my experience ill-equipped for the task including Gangadean himself. The arguments are just not there.

Finally, a third option is to fight for a new conceptual distinction and shall be the topic of this post. This was actually suggested to me once by Anderson although in a very tentative way. I was raising some of the very issues that I've explored in this blog about the worry of skepticism which seems to follow from Gangadean's demanding theory of knowledge. It was then suggested by Anderson that perhaps there were really two kinds of knowledge: one requires certainty and the other doesn't. We can have knowledge of the former kind of only "the most basic things" and yet we have knowledge of the latter sort (the one that doesn't require certainty) of a larger scope of propositions---you know, like everyday propositions (e.g., that I have hands).

To make things easier let's label these two kinds of knowledge thusly: Gangadeanian knowledge which requires epistemic certainty = G-Knowledge (or in verb form, G-knows) and the latter sort we'll call E-Knowledge (or E-knows, in verb form) which is short for "everyday-knowledge." Here are some critical questions that we should consider in light of this proposal.

1) Does it actually solve any of the problems it's supposed to?

2) Is it independently motivated so as not to be ad hoc?

3) How do we draw the boundary line between the things we can only E-Know and that which we can G-know?

With respect to 1), if there were two kinds of knowledge constituted by different evidentiary standards, then it would seem that some of the bite of skeptical worries is assuaged. So that's a virtue of the proposal. As I've argued before, you can't know much of anything on Gangdean's theory of knowledge. A wife couldn't possibly know that she is waking up next to her husband each morning because it's at least possible that he was switched at night with a facsimile--or that her perceptual faculties are playing a trick or her (e.g., she's hallucinating that it's her husband). That for Gangadean means she could not know that the being next to her is her husband. That makes the theory silly of course. By suggesting that there are actually two kinds of knowledge we can make Gangadean's theory seem a little less silly in this way. The idea would be that while you can't G-know things like, "I am not hallucinating right now" you can at least E-Know it. Remember E-knowledge has lower standards than G-knowledge or so the argument would go.

Unfortunately for the Gangadeanian wielding this distinction, it solves one set of problems only to introduce new ones. The problem is that by proliferating kinds of knowledge, we run into a value question. Why should we care about G-knowledge at all? If both E-knowledge and G-knowledge are species of knowledge, then why is one to be desired over the other particularly if one has far more applications than the other. Can't a person, even according to the two-kinds of knowledge-Gangdeanian, E-know that God exists on the basis of intuition or experience or by testimony or evidentialist approaches to apologetics? And if so, why do they need anything else? In other words, we need an argument explaining just why G-knows, given how hard it is to come by, is desirable, valuable, or necessary. Why must a person G-knows that God exists rather than merely E-knowing that it is so? Of course, there's a value question about knowledge even when we're only thinking about one kind of knowledge and a significant body of literature on the topic, but introducing another kind only makes the question more pressing particularly when the claim is that we can know some things in one sense, but not the other.

As to 2), the quick answer is that it's more certainly ad hoc. Anderson tentatively proposed it in a conversation in order to save his theory from a serious problem. Suppose it solves the very problem it's purported to solve--- that doesn't make it true or give us reason to think it's true. We need independent grounds for that. I could come up with a very different theory of knowledge and in the face of counterexamples suggest more and more kinds of knowledge--but that doesn't make my theory or the patches true. This is why it's important to ask for independent motivations i.e., reasons to believe that there are two kinds of knowledge which have nothing to do with the problem that it purports to get around in order to preserve Gangadean's theory of knowledge (which is the very thing in question).

3) The issue here is how we can determine which things are in principle E-knowable, but not G-knowable. If you could do this then you could figure out just which things are G-knowable. It's no good in the current context for the Gangadeanian to say that "the most basic things" are sort of by definition, G-knowable. Here's why. Gangadean's argument for his theory of knowledge is predicated on the idea that skepticism follows if the basic things are not clear (G-knowable). But the two-kinds of knowledge thesis is meant to undermine the skeptical worries in the first place. So skepticism at least of one sort is defanged but out goes with it the transcendental argument for the necessity of clarity of basic things (i.e., the G-knowability of basic things).

Even if the basic things aren't clear (in the G-knowable sense), admitting that there are two kinds of knowledge allows that the basic things could be clear in the E-knowable sense. That makes the transcendental argument that Gangadeanians favor no good, here. This brings us back to our discussion in 1). What makes G-knowledge worthwhile? Valuable? Desirable? Why should we care about it at all? Why not just stick with E-knowledge of both the less basic and the more basic? It's knowledge after all!

Even if the basic things aren't clear (in the G-knowable sense), admitting that there are two kinds of knowledge allows that the basic things could be clear in the E-knowable sense. That makes the transcendental argument that Gangadeanians favor no good, here. This brings us back to our discussion in 1). What makes G-knowledge worthwhile? Valuable? Desirable? Why should we care about it at all? Why not just stick with E-knowledge of both the less basic and the more basic? It's knowledge after all!

Tuesday, June 6, 2017

An egregious argument for the veracity of the bible.

My apologies for my absence as of late--my days have been quite busy. Anyway, today I found myself perusing the page of the Tempe, AZ chapter of Ratio Christi (which is run by a Gangadeanian) and I encountered the following argument.

1. God’s existence and God’s moral law are clear to reason.

2. Humans have failed to know God and obey the moral law.

3. God cannot forgive without atonement.

4. Only the Bible shows how sin is atoned for.

5. Therefore, the Bible is true.

In my view, the Gangadeanian worldview is fraught with bad arguments. But this one is particularly offensive. In fact, it was this very bad argument that was sort of the "last straw" for me when I was still a member of the congregation. That is, it was this very issue concerning how it is that we could know (with Gangadeanian certainty) that the bible was the word of God (i.e., genuine special revelation) which eventually got me kicked out of the church. It was this issue initially which lead to discussions with Gangadean and others where I was able to see just how spurious Gangadean's reasoning really is and how closed off he is to having his basic beliefs examined critically. In a way, I owe a lot to this bad argument.

So onto the content. The main issue that arises is that Gangadean's impossible epistemic standards for knowledge, held consistently, leads to skepticism. One area that this skepticism will be most strongly felt for the Christian is on the matter of the veracity of scripture. So the Gangadeanian offers an argument to show how we can come to know (with Gangadeanian certainty) that the bible contains only truths. Note, I'm setting aside the complicated question about what all is entailed by the claim that the bible is "special revelation" or "divinely inspired." After all, it isn't obvious that divinely inspired text needs to be infallible or inerrant--likewise, infallibility and inerrancy of a particular text is also not sufficient to make it "divinely inspired." For now let's just focus on the infallibility claim.

My claim is that the Gangadeanian argument above, call it the egregious argument for the veracity of the bible (or the EAVB for short) is both invalid and also such that a Gangadeanian ought not to accept any of the premises as true, based Gangadean's own professed epistemic standards.

If you've been around these parts you know that premise 1) is false. God's existence is not "clear to reason". Perhaps it seems subjectively obvious to Gangadeanians, but that's not enough. Gangadean simply fails to prove that the God of Christian theism exists at least according to his own standards of proof. I won't get into much detail on this point since I've already written about it, but basically he takes for granted the assumption that reality is composed only of 2 possible substances, matter and spirit. He argues against the eternality of matter and, by way of disjunctive syllogism, he "deduces" that what is eternal must be spirit. But he never bothers to prove the dichotomy (all is either spirit or matter and nothing else) to begin with. Furthermore, his argument against the eternality of matter (really he's got to show that it's logically impossible for matter to be eternal) are also bad. He appeals to empirical findings which by their very nature are not going to provide proofs in the sense that he demands. He merely claims that we lack positive reason to believe that matter is eternal which isn't the same as having shown that matter can't possibly be eternal (compare: I don't have any evidence to believe that bigfoot exists vs. it's logically impossible for bigfoot to exist). So much for premise 1).

At the risk of being pedantic, let me note that premise 2) is clumsily stated. It reads, 'Humans have failed to know God and obey the moral law.' Philosophers and linguists call that a generic statement and this is an issue about quantification. What premise 2 doesn't say is "All humans have failed to know God". Nor does it say "at least one human has failed to know God...". All generics like, 'Dogs have four legs' are weird because they don't fit nicely within the scheme of quantifiers in standard logic. Just ask yourself how many dogs need to have 4 legs in order for the statement, 'Dogs have four legs' to be true? Half? 1 more than half? 1/3? Who knows...

Surely, though, the Gangadeanians believe that "All humans have failed to know God..." I know this not only from personal conversations, but also because being the Calvinists that they are, they believe in doctrine of total depravity. But this gives way to a problem. If the argument above (EAVB) is given in order to prove that the Bible contains only truths, then we can't assume any of its teachings to be true in giving the argument--that would be to assume what you need to prove. Now Calvinists generally adopt the 5 points of Calvinism based on a certain reading of the bible which presupposes the bible is true (at least the pertinent "proof texts"). What this means is that for a Gangadeanian to believe that all humans have failed to know God, they must have independent (non-scripture based) proof that all humans (present, past, future) will fail/have failed to know God and to obey the moral law. But how can Gangadean, his followers, or anyone for that matter come to prove a thing like that?

Notice what won't work. I can already hear a Gangadeanian appealing to the presence of natural evil in particular, in the form of physical death. If we can know that all humans are mortal (assuming we could know a thing like that with Gangadeanian certainty), then we can know that all humans are afflicted by natural evil, and this shows that they are basically sinners which is failing to obey the law and further this is fundamentally failing to know God despite its being clear that God exists.

There are at least two problems with this approach. As I flagged above, they would need to prove that all humans are mortal (past, present, and future). I'm not saying I doubt this claim. I assign a very high credence to the proposition that all humans are mortal. That's not the point. All I'm saying is that my grounds for believing this (induction or some presumption that it's part of the concept of a biological entity that it is mortal) doesn't satisfy the Gangadean's demands for certainty. So I'd press Gangadean for a proof from indubitable premises to the conclusion that all humans are mortal (i.e., a proof for the claim that all humans are afflicted by natural evil as a call back from moral evil).

Second, and more substantially, as I've already shown, Gangadean helps himself to lots of assumptions when he speaks of the function and nature of natural evil (and it's relation to moral evil) in his failed attempt at giving a theodicy. These assumptions are load-bearing, but they remain unsupported assumptions and so ultimately fall under pressure. So to move from 'all humans get old and die' to 'all humans have sinned' is tenuous at best. Of course, premise 2) could be true (we can say that about a lot of propositions), but the point is Gangadean and his standards for justified belief and knowledge require that he prove its truth beyond all doubt. So the Gangadeanian ought not to accept premise 2).

Premise 3) God cannot forgive without atonement.

I've called into question this premise before as well. What I noticed is that Gangadean "supports" claims like this on the basis of some mysterious lexicon of the English language. Basically, Gangadean has in mind a particular (and quirky) notion of justice. But as I've shown elsewhere, there's no way for him to prove that his concept or definition of 'justice' is the correct one. He can indoctrinate his followers with his special dictionary till the cows come home, but surely he doesn't get to decide the meaning of a word in a given language or the content of a concept by fiat! Nor should we assume he has some privileged access to the "correct concept" or "correct definition."

More importantly, his views on the nature of divine justice are simply confused. As I've already argued elsewhere, a priori, there's no reason why God cannot forgive without atonement. The whole Christian idea of divine grace via the passion of Christ is anything but the kind of justice that Gangadean has in mind which is basically "treating things according to their kind" or "treating like with like." As I've posed before, how can the sins of the world be "justly" taken on by a single person (Jesus) who is without sin? That is far from "treating like with like." So premise 3) likewise seems false. One thing to keep in mind in thinking through the appropriateness of this premise (and the others) is this: in the current dialectic Gangadean can't dip into the bible as proof texts to support it--that would be question begging since the truth of the claims that make up the bible is the very thing at issue.

Premise 4) Only the Bible shows how sin is atoned for.

This is just plain silly. How on earth can anybody know that the bible is the only written text in the entire world/universe (both past, present, and future) which shows how "sins are atoned for"? Remember Gangadean requires certainty for knowledge. On this standard, it's hard to see how anyone could know that premise 4). I'm merely asking him to make good on his own requirements! The answer of course is that there's simply no way to know premise 4) with any amount of certainty because it's an empirical claim!

Furthermore, as I've raised before, there's a problem of criteria. On Gangadean's worldview, we need the bible (or special revelation) to tell us how divine mercy interacts with divine justice--that's the whole bit about "how our sins are atoned for". The idea is that we can't possibly figure this stuff out by reason alone. It was not possible for us to connect the dots from general revelation (what we know from reason alone) to the contents of the gospel message and that's why we have the good news given to us via divine revelation. Otherwise, if we could reason to it all, we wouldn't need a message from God in the first place! But if we can't reason to the correct account of how we are to be forgiven of our sins, how are we to know (with certainty) what it is that we're looking for? That is, how are we to recognize the correct account as the correct one? It seems like we need to know what makes for a correct account of the atonement of our sins in order to recognize the correct one as such, but if we know what makes for a correct account, then we don't need special revelation.

Finally, the argument above is simply invalid. That is to say, the premises, even if they were true wouldn't entail the truth of the conclusion. For one thing, "the bible is true" is again a kind of generic statement. Presumably, what the author of the EAVB intends is that every claim in the bible is true. But it's not clear how the truth of the premises would entail that. See here where I discuss this point and others I've raised above in more detail. Since validity is necessary for soundness, the argument is unsound. So what you have here is the worst kind of argument--sort of the "opposite" of a sound argument. It's invalid and all the premises are false.

1. God’s existence and God’s moral law are clear to reason.

2. Humans have failed to know God and obey the moral law.

3. God cannot forgive without atonement.

4. Only the Bible shows how sin is atoned for.

5. Therefore, the Bible is true.

In my view, the Gangadeanian worldview is fraught with bad arguments. But this one is particularly offensive. In fact, it was this very bad argument that was sort of the "last straw" for me when I was still a member of the congregation. That is, it was this very issue concerning how it is that we could know (with Gangadeanian certainty) that the bible was the word of God (i.e., genuine special revelation) which eventually got me kicked out of the church. It was this issue initially which lead to discussions with Gangadean and others where I was able to see just how spurious Gangadean's reasoning really is and how closed off he is to having his basic beliefs examined critically. In a way, I owe a lot to this bad argument.

So onto the content. The main issue that arises is that Gangadean's impossible epistemic standards for knowledge, held consistently, leads to skepticism. One area that this skepticism will be most strongly felt for the Christian is on the matter of the veracity of scripture. So the Gangadeanian offers an argument to show how we can come to know (with Gangadeanian certainty) that the bible contains only truths. Note, I'm setting aside the complicated question about what all is entailed by the claim that the bible is "special revelation" or "divinely inspired." After all, it isn't obvious that divinely inspired text needs to be infallible or inerrant--likewise, infallibility and inerrancy of a particular text is also not sufficient to make it "divinely inspired." For now let's just focus on the infallibility claim.

My claim is that the Gangadeanian argument above, call it the egregious argument for the veracity of the bible (or the EAVB for short) is both invalid and also such that a Gangadeanian ought not to accept any of the premises as true, based Gangadean's own professed epistemic standards.

If you've been around these parts you know that premise 1) is false. God's existence is not "clear to reason". Perhaps it seems subjectively obvious to Gangadeanians, but that's not enough. Gangadean simply fails to prove that the God of Christian theism exists at least according to his own standards of proof. I won't get into much detail on this point since I've already written about it, but basically he takes for granted the assumption that reality is composed only of 2 possible substances, matter and spirit. He argues against the eternality of matter and, by way of disjunctive syllogism, he "deduces" that what is eternal must be spirit. But he never bothers to prove the dichotomy (all is either spirit or matter and nothing else) to begin with. Furthermore, his argument against the eternality of matter (really he's got to show that it's logically impossible for matter to be eternal) are also bad. He appeals to empirical findings which by their very nature are not going to provide proofs in the sense that he demands. He merely claims that we lack positive reason to believe that matter is eternal which isn't the same as having shown that matter can't possibly be eternal (compare: I don't have any evidence to believe that bigfoot exists vs. it's logically impossible for bigfoot to exist). So much for premise 1).

At the risk of being pedantic, let me note that premise 2) is clumsily stated. It reads, 'Humans have failed to know God and obey the moral law.' Philosophers and linguists call that a generic statement and this is an issue about quantification. What premise 2 doesn't say is "All humans have failed to know God". Nor does it say "at least one human has failed to know God...". All generics like, 'Dogs have four legs' are weird because they don't fit nicely within the scheme of quantifiers in standard logic. Just ask yourself how many dogs need to have 4 legs in order for the statement, 'Dogs have four legs' to be true? Half? 1 more than half? 1/3? Who knows...

Surely, though, the Gangadeanians believe that "All humans have failed to know God..." I know this not only from personal conversations, but also because being the Calvinists that they are, they believe in doctrine of total depravity. But this gives way to a problem. If the argument above (EAVB) is given in order to prove that the Bible contains only truths, then we can't assume any of its teachings to be true in giving the argument--that would be to assume what you need to prove. Now Calvinists generally adopt the 5 points of Calvinism based on a certain reading of the bible which presupposes the bible is true (at least the pertinent "proof texts"). What this means is that for a Gangadeanian to believe that all humans have failed to know God, they must have independent (non-scripture based) proof that all humans (present, past, future) will fail/have failed to know God and to obey the moral law. But how can Gangadean, his followers, or anyone for that matter come to prove a thing like that?

Notice what won't work. I can already hear a Gangadeanian appealing to the presence of natural evil in particular, in the form of physical death. If we can know that all humans are mortal (assuming we could know a thing like that with Gangadeanian certainty), then we can know that all humans are afflicted by natural evil, and this shows that they are basically sinners which is failing to obey the law and further this is fundamentally failing to know God despite its being clear that God exists.

There are at least two problems with this approach. As I flagged above, they would need to prove that all humans are mortal (past, present, and future). I'm not saying I doubt this claim. I assign a very high credence to the proposition that all humans are mortal. That's not the point. All I'm saying is that my grounds for believing this (induction or some presumption that it's part of the concept of a biological entity that it is mortal) doesn't satisfy the Gangadean's demands for certainty. So I'd press Gangadean for a proof from indubitable premises to the conclusion that all humans are mortal (i.e., a proof for the claim that all humans are afflicted by natural evil as a call back from moral evil).

Second, and more substantially, as I've already shown, Gangadean helps himself to lots of assumptions when he speaks of the function and nature of natural evil (and it's relation to moral evil) in his failed attempt at giving a theodicy. These assumptions are load-bearing, but they remain unsupported assumptions and so ultimately fall under pressure. So to move from 'all humans get old and die' to 'all humans have sinned' is tenuous at best. Of course, premise 2) could be true (we can say that about a lot of propositions), but the point is Gangadean and his standards for justified belief and knowledge require that he prove its truth beyond all doubt. So the Gangadeanian ought not to accept premise 2).

Premise 3) God cannot forgive without atonement.

I've called into question this premise before as well. What I noticed is that Gangadean "supports" claims like this on the basis of some mysterious lexicon of the English language. Basically, Gangadean has in mind a particular (and quirky) notion of justice. But as I've shown elsewhere, there's no way for him to prove that his concept or definition of 'justice' is the correct one. He can indoctrinate his followers with his special dictionary till the cows come home, but surely he doesn't get to decide the meaning of a word in a given language or the content of a concept by fiat! Nor should we assume he has some privileged access to the "correct concept" or "correct definition."

More importantly, his views on the nature of divine justice are simply confused. As I've already argued elsewhere, a priori, there's no reason why God cannot forgive without atonement. The whole Christian idea of divine grace via the passion of Christ is anything but the kind of justice that Gangadean has in mind which is basically "treating things according to their kind" or "treating like with like." As I've posed before, how can the sins of the world be "justly" taken on by a single person (Jesus) who is without sin? That is far from "treating like with like." So premise 3) likewise seems false. One thing to keep in mind in thinking through the appropriateness of this premise (and the others) is this: in the current dialectic Gangadean can't dip into the bible as proof texts to support it--that would be question begging since the truth of the claims that make up the bible is the very thing at issue.

Premise 4) Only the Bible shows how sin is atoned for.

This is just plain silly. How on earth can anybody know that the bible is the only written text in the entire world/universe (both past, present, and future) which shows how "sins are atoned for"? Remember Gangadean requires certainty for knowledge. On this standard, it's hard to see how anyone could know that premise 4). I'm merely asking him to make good on his own requirements! The answer of course is that there's simply no way to know premise 4) with any amount of certainty because it's an empirical claim!

Furthermore, as I've raised before, there's a problem of criteria. On Gangadean's worldview, we need the bible (or special revelation) to tell us how divine mercy interacts with divine justice--that's the whole bit about "how our sins are atoned for". The idea is that we can't possibly figure this stuff out by reason alone. It was not possible for us to connect the dots from general revelation (what we know from reason alone) to the contents of the gospel message and that's why we have the good news given to us via divine revelation. Otherwise, if we could reason to it all, we wouldn't need a message from God in the first place! But if we can't reason to the correct account of how we are to be forgiven of our sins, how are we to know (with certainty) what it is that we're looking for? That is, how are we to recognize the correct account as the correct one? It seems like we need to know what makes for a correct account of the atonement of our sins in order to recognize the correct one as such, but if we know what makes for a correct account, then we don't need special revelation.

Finally, the argument above is simply invalid. That is to say, the premises, even if they were true wouldn't entail the truth of the conclusion. For one thing, "the bible is true" is again a kind of generic statement. Presumably, what the author of the EAVB intends is that every claim in the bible is true. But it's not clear how the truth of the premises would entail that. See here where I discuss this point and others I've raised above in more detail. Since validity is necessary for soundness, the argument is unsound. So what you have here is the worst kind of argument--sort of the "opposite" of a sound argument. It's invalid and all the premises are false.

Sunday, April 2, 2017

Worth a Watch.

This video is worth a watch. It's a brief TED talk given by Megan Phelps-Roper who left the notorious Westboro Baptists. Having been raised from birth to parrot, believe and live by a particular worldview, it's pretty incredible that she was able to have a change of mind as a result of certain virtual relationships and dialogues. Even though this meant that she was excommunicated by her own family. I've been hearing about similar stories lately (Here's a story of a White Supremacist that had a dramatic change of mind and heart as a result of his encounters in college). In some ways it's a bit encouraging that people can change despite having very deeply held views and despite belonging to extremely isolationist groups.

Roper's talk was also a good reminder for me to continue working on my approach in dialogues--to shed more light and generate less heat. I also like what she says at the end about how we tend to think our own positions are self-evident or obvious and not in need of explanation.

Roper's talk was also a good reminder for me to continue working on my approach in dialogues--to shed more light and generate less heat. I also like what she says at the end about how we tend to think our own positions are self-evident or obvious and not in need of explanation.

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Anderson's fallibility with respect to Fallibilism

It looks like Anderson is making use of some of our exchanges in his courses now. That's partially encouraging, but I suspect that the strawman fallacy abounds. I say this because Gangadeanians in general seem to have a hard time understanding my views as opposed to mere caricatures. This is largely due to the fact that they haven't done their due diligence. They never cared to try and understand because in my experience they tend to be quick to the defense which seems to cloud their abilities to assess things with a clear head.

Anderson in a recent post speaks of fallibilism about knowledge. One should note at the outset that the fallibilism that I am committed to is something like moderate or weak fallibilism--which is just the thesis that knowledge doesn't require maximal justification or epistemic certainty. That's just an existential thesis that might be stated formally in the following way:

Now to be fair, I supplement this thesis with another. I also think that we don't have maximal justification about most, if not all of our beliefs and by extension, for much or all of what we know. But I'm far less committed to this position. In many of my exchanges with Gangadeanians, I'm happy to not presuppose. The other thing to note is that this second thesis is much weaker than Gangadeanians often attribute to me again due to their lack of due-diligence. To say that we don't have certainty is a claim about actuality. It's not the stronger claim (nor does it entail) that certainty is impossible. To see the contrast, I might say that I don't think that people actually live beyond 140 years, but that doesn't imply that it's impossible for people to live longer.

As it pertains to the Gangadeanian worldview, what I claim is that even if certainty is in principle possible, they haven't shown us a consistent way of ascertaining it. At the "most basic level," they just use intuitions and conveniently switch the label on us. One upshot: suppose that Gangadean were to somehow successfully show that we must have certainty without appealing to intuitions under a different label and without begging the question. Still, that's not the same as showing us how it is that we can attain certainty. Those are just two different things. Now I don't think he's even tried to show us that we need certainty as opposed to simply asserting so much. It's an axiom of his system really (though he wouldn't be caught dead using such a term).

So to be clear, certainty may be possible, but that's not to say very much. If it's a remote enough of a possibility, then who really cares about it? Certainty might even be necessary for certain purposes (though I don't believe this for a minute), but again that's not to have shown much.

The nagging questions are how it is that we can be certain when we have attained certainty? How do we know when something is self-attesting as opposed to merely seeming to us to be self-attesting?Further, is the question that moves beyond possibility to actuality (i.e., can we have certainty vs. do we actually have it?). Further, why does the fact that a proposition is self-attesting count as having achieved certainty of it? You might be tempted to think something like, "that's just what 'self-attesting' means." But how are you so certain that the phrase 'self-attesting' even has an extension? How are you certain that it denotes anything? The Gangadeanian might in turn be tempted to respond with, "well you're using the terms 'self-attesting' and asking how we can be certain that something is self-attesting and so you must be presupposing that it has extension." But that's just confusing the terms of the debate. Here's my response: I'm merely using the word because you've introduced it. For all I've said, it could just as easily be replaced by a variable like 'X' that may or may not have any referent. It's your job to show us that it does!

Yes, I doubt we have certainty of much of anything, which again isn't the same thing as suggesting that certainty is impossible.

Why am I skeptical that we actually have certainty over what we know? Well it's a really high bar. If we equate certainty with maximal justification (as the Gangadeanians do) then this amounts to it not being possible to have more justification for the proposition in question--your epistemic position, as it were, as it regards that proposition couldn't possibly be improved. For the theists among us, you might say that your epistemic position with respect to the proposition for which you have certainty, is no worse than that of God's position. And that just seems crazy to me. It seems to me that we can always improve our epistemic position with respect to what we know even in the things we feel quite certain about (note there's a big difference between mere psychological certainty and epistemic certainty and it's the latter that we're interested in, but I suspect Gangadeanians sometimes conflate to two).

To this the Gangadeanians will no doubt argue in the following manner. We must have certainty, to question anything, including whether we have certainty. Without clarity at the basic level, thinking is not possible and neither is questioning (which presupposes thoughts). The problem is, this is an unproven assumption. As I've pointed out many times in the past, there's just no reason given to accept the claim that we must have certainty for thought or questioning to be possible. It just seems like an intuition that supports their entire worldview.

Anyway, I noticed that Anderson in his post about fallibilism had some of the following "study questions". I'll speak briefly about them since they point to just how mistaken is his understanding of my position as well as fallibilism in general.

What does it mean for a law to be self-attesting? Does the fallibilist believe anything is self-attesting? How could one prove that nothing is self-attesting?

One thing to note here is that it's strange that the fallibilist would be at all interested in trying to prove that nothing is self-attesting. The fallibilist would say that we can know things without proof. Moreover, many fallibilists are externalists about knowledge. So why would they feel any need to prove that nothing is self-attesting in the first place (do we need more than knowledge of things)? This smells like a slip on Anderson's part where he's smuggling in infallibilism + internalism in evaluating fallibilism which is question-begging.

Can a fallibilist be certain that a statement he made is actually the statement he made? Must a fallibilist he concerned for intellectual consistency?

Here, too again is the same sort of slip as above. Why would the fallibilist need or desire certainty about the statements they are making?! A fallibilist would say that they can know what statements they are making and it doesn't require certainty. So what more do you want? Again, he's assuming infallibilist norms in order to in effect, argue against fallibilism which is obviously begging the question.

Anderson in a recent post speaks of fallibilism about knowledge. One should note at the outset that the fallibilism that I am committed to is something like moderate or weak fallibilism--which is just the thesis that knowledge doesn't require maximal justification or epistemic certainty. That's just an existential thesis that might be stated formally in the following way:

Weak Fallibilism: there is at least one subject S and one proposition P such that S knows that P, without having maximal justification for P.'Existential' above denotes the quantifier 'at least some' which is to be contrasted with (is sometimes called the 'subalternation' of) to the quantifier 'all'. In other words, I think that we can know things without having maximal justification.

Now to be fair, I supplement this thesis with another. I also think that we don't have maximal justification about most, if not all of our beliefs and by extension, for much or all of what we know. But I'm far less committed to this position. In many of my exchanges with Gangadeanians, I'm happy to not presuppose. The other thing to note is that this second thesis is much weaker than Gangadeanians often attribute to me again due to their lack of due-diligence. To say that we don't have certainty is a claim about actuality. It's not the stronger claim (nor does it entail) that certainty is impossible. To see the contrast, I might say that I don't think that people actually live beyond 140 years, but that doesn't imply that it's impossible for people to live longer.

As it pertains to the Gangadeanian worldview, what I claim is that even if certainty is in principle possible, they haven't shown us a consistent way of ascertaining it. At the "most basic level," they just use intuitions and conveniently switch the label on us. One upshot: suppose that Gangadean were to somehow successfully show that we must have certainty without appealing to intuitions under a different label and without begging the question. Still, that's not the same as showing us how it is that we can attain certainty. Those are just two different things. Now I don't think he's even tried to show us that we need certainty as opposed to simply asserting so much. It's an axiom of his system really (though he wouldn't be caught dead using such a term).

So to be clear, certainty may be possible, but that's not to say very much. If it's a remote enough of a possibility, then who really cares about it? Certainty might even be necessary for certain purposes (though I don't believe this for a minute), but again that's not to have shown much.

The nagging questions are how it is that we can be certain when we have attained certainty? How do we know when something is self-attesting as opposed to merely seeming to us to be self-attesting?Further, is the question that moves beyond possibility to actuality (i.e., can we have certainty vs. do we actually have it?). Further, why does the fact that a proposition is self-attesting count as having achieved certainty of it? You might be tempted to think something like, "that's just what 'self-attesting' means." But how are you so certain that the phrase 'self-attesting' even has an extension? How are you certain that it denotes anything? The Gangadeanian might in turn be tempted to respond with, "well you're using the terms 'self-attesting' and asking how we can be certain that something is self-attesting and so you must be presupposing that it has extension." But that's just confusing the terms of the debate. Here's my response: I'm merely using the word because you've introduced it. For all I've said, it could just as easily be replaced by a variable like 'X' that may or may not have any referent. It's your job to show us that it does!

Yes, I doubt we have certainty of much of anything, which again isn't the same thing as suggesting that certainty is impossible.

Why am I skeptical that we actually have certainty over what we know? Well it's a really high bar. If we equate certainty with maximal justification (as the Gangadeanians do) then this amounts to it not being possible to have more justification for the proposition in question--your epistemic position, as it were, as it regards that proposition couldn't possibly be improved. For the theists among us, you might say that your epistemic position with respect to the proposition for which you have certainty, is no worse than that of God's position. And that just seems crazy to me. It seems to me that we can always improve our epistemic position with respect to what we know even in the things we feel quite certain about (note there's a big difference between mere psychological certainty and epistemic certainty and it's the latter that we're interested in, but I suspect Gangadeanians sometimes conflate to two).

To this the Gangadeanians will no doubt argue in the following manner. We must have certainty, to question anything, including whether we have certainty. Without clarity at the basic level, thinking is not possible and neither is questioning (which presupposes thoughts). The problem is, this is an unproven assumption. As I've pointed out many times in the past, there's just no reason given to accept the claim that we must have certainty for thought or questioning to be possible. It just seems like an intuition that supports their entire worldview.

Anyway, I noticed that Anderson in his post about fallibilism had some of the following "study questions". I'll speak briefly about them since they point to just how mistaken is his understanding of my position as well as fallibilism in general.

What does it mean for a law to be self-attesting? Does the fallibilist believe anything is self-attesting? How could one prove that nothing is self-attesting?

One thing to note here is that it's strange that the fallibilist would be at all interested in trying to prove that nothing is self-attesting. The fallibilist would say that we can know things without proof. Moreover, many fallibilists are externalists about knowledge. So why would they feel any need to prove that nothing is self-attesting in the first place (do we need more than knowledge of things)? This smells like a slip on Anderson's part where he's smuggling in infallibilism + internalism in evaluating fallibilism which is question-begging.

Can a fallibilist be certain that a statement he made is actually the statement he made? Must a fallibilist he concerned for intellectual consistency?

Here, too again is the same sort of slip as above. Why would the fallibilist need or desire certainty about the statements they are making?! A fallibilist would say that they can know what statements they are making and it doesn't require certainty. So what more do you want? Again, he's assuming infallibilist norms in order to in effect, argue against fallibilism which is obviously begging the question.

Is fallibilism a neutral position from which to criticize others or does it have presuppositions that need to be identified and proven to be true?

And yet again, same mistake! The fallibilist isn't necessarily a neutral position, but neither does it aim to prove things like the infallibilist of Gangadean's vintage. So why would the fallibilist feel the need to prove it's own assumptions if certainty isn't needed for knowledge? The fallibilist allows that they have assumptions like everyone else does, and even goes so far as to say that these assumptions can count as knowledge without proof. So how is this question supposed to suggest an inconsistency with fallibilism?

A couple of elementary lesson in argumentation do result from this exploration.

1) You shouldn't use premises that presuppose that your opponent's view is wrong in order to show that their position is wrong.

2) If you want to point out an inconsistency in your opponents position, you should stick to premises that they accept. You shouldn't characterize their view as having an assumption that you accept, but they that reject.

And yet again, same mistake! The fallibilist isn't necessarily a neutral position, but neither does it aim to prove things like the infallibilist of Gangadean's vintage. So why would the fallibilist feel the need to prove it's own assumptions if certainty isn't needed for knowledge? The fallibilist allows that they have assumptions like everyone else does, and even goes so far as to say that these assumptions can count as knowledge without proof. So how is this question supposed to suggest an inconsistency with fallibilism?

A couple of elementary lesson in argumentation do result from this exploration.

1) You shouldn't use premises that presuppose that your opponent's view is wrong in order to show that their position is wrong.

2) If you want to point out an inconsistency in your opponents position, you should stick to premises that they accept. You shouldn't characterize their view as having an assumption that you accept, but they that reject.

Monday, January 2, 2017

Ganagdean and Infinite Justice and Mercy

What does God's justice demand? Well, what is the nature of divine justice? And how are we to know what divine justice is?

There are various theories of justice and likewise various theories of infinite/divine justice. Many Christians take themselves to have a rather strong grasp of divine justice since they often cite it to answer objections about the doctrine of eternal damnation, and the need for atonement. Gangadeanians are no exception. They believe that divine justice requires that sin not be set aside, but rather must be accounted for. For God to simply overlook or forgive wrongdoing would be to violate his nature as divinely just. So sin must have consequences.

As Gangadeanians see it, the wages of sin are spiritual death which is failing to know what is clear. This is because at root sin is the failure to seek to know what is clear (to live contrary to what it means to be a rational animal/human). Failure to seek leads to ignorance. It's not clear what the nature of the connection is-- but they claim that there is an intrinsic link between failing to seek and failing to know what is clear. I'm skeptical of this purported conceptual connection because it isn't obvious to me that it is logically impossible for a human to know without seeking. I wouldn't limit God to that extent--if God so pleased, it seems to me that it's at least logically possible for him to give a human knowledge directly.

So ignorance of basic things = the wages of sin for the Gangadeanians. It's a very cognitive notion.

But they also believe that God is also infinitely merciful. Gangadeanians believe that even though God cannot (i.e., it's a logical impossibility) merely overlook sin because on their view, this would be incompatible with God's divine justice, God is also merciful. So he must save some (more on this below). But what does it mean to save some? Well, it requires that God forgive some of their sins. It isn't that God ignores the sin, but God atones for it or else again his divine justice would be threatened.

As you're thinking through these lines of reasoning, it's important to keep the following in mind in order to keep the Gangadeanians honest. Often it's not obvious just which claims are supposed to be known via general revelation (via reason alone) and which parts are known via special revelation (scripture). They want to argue for a particular fundamentalist brand of Christianity, but some of it comes from reason alone and others from scripture.

In the first place, the Gangadeanians are claiming to have quite a bit of insight into what God's justice consists of--or else much of the reasoning above won't make sense. But just how do they know that divine justice cannot merely set aside sin? How do they know that God is infinitely just (in just the way that they define 'justice')? How do they know that God is infinitely merciful? How do they know what infinite mercy looks like? In fact, answers to these questions should not appeal to scripture. This is because it is part of their argument for the bible as God's word--so that would be question-begging.

On more than one occasion, I've spoken to a Gangadeanian who assures me that justice consists in "treating likes as like" or in other words an "eye for an eye" notion of justice. People get what they deserve---there are consequences to sin just as there are consequences for good works. And according to Gangadean, divine justice is following this "system" perfectly.

Notice, that this doesn't answer the epistemological question: how do you know what divine justice is? It presupposes an answer and moves to offer a metaphysical theory about what divine justice consists of. This is an important point because it's just another juncture at which Gangadeanians appeal to intuition--they have a sense of what justice is and take it for granted as the correct one (just like they do with their theory of knowledge and any number of other concepts).

But even if we grant them this (and we really shouldn't since they are after epistemic certainty), more problems emerge. Insofar as they have this "eye for an eye" notion of divine justice in mind, and they think that it helps them affirm the bible as the word of God, they should find themselves in quite a quandary. Sure there are instances of "treating likes as likes" in scripture, but then you've got that whole bit about Jesus dying for the sins of his people. That isn't treating "likes as likes" and it's anything but "eye for an eye." It's fairly obvious that God incarnate who is without sin, dying for say billions of unrepentant sinners and thereby preventing them from reaping the intrinsic consequences of their sins is far from treating 'a' as 'a.' By definition, the regenerate don't get what they deserve. They simply don't reap what they sow. They reap infinitely better than they have sown.

Thus insofar as the Gangadeanian worldview suggests we can deduce from reason alone the claim that the bible is the word of God, based on their notion of divine justice, it's actually a non-starter. Their notion of divine justice should have them rejecting the bible (qua special revelation) outright. Alternatively, they may reject their starting notion of divine justice--but other problems will emerge for their worldview e.g., why is there are need for SR? and why is atonement only limited?.

What about their notion of divine mercy? Again, the same problems emerge as with justice. There are analogous epistemological questions: how do you know that God is infinitely merciful? How do you know what infinite mercy even looks like? Notice, again it would be question-begging to presuppose the bible has any authority at this point--since their claim that God is infinitely merciful (as well as what that looks like) must first be settled since it serves as a premise to their argument for the bible as the genuine word of God. But how reason alone, and considerations of whether something must be eternal, gets them to affirming that God is infinitely merciful, or even what it is that infinite mercy (or mercy at all) should look like (i.e., what the nature of mercy is) is beyond me. Interestingly, I've yet to hear Gangadean's theory of mercy let alone mercy of the infinite sort.

The way that Gangadean frames things then is that he's got a particular notion of divine justice and divine mercy in mind which he claims you can derive from reason alone (just by thinking). You can't and need not appeal to scripture at this point for any insight. Instead there are sound arguments starting from his argument for "something must be eternal" which can provide you with a proof that God is infinitely just and merciful (in just the way that Gangadean defines these things) and then ultimately to the conclusion that the bible is the word of God. I find the prospects of such deductions to be ludicrous. More importantly, Gangadean and his people are super shady about presenting them. My guess is that they don't actually have any such arguments. Instead their tactic is to "get more basic" and try to find a way to label you as someone that denies reason.

My take is that we have intuitive senses of justice and mercy--there are certain phenomena that we have contingently come to call 'justice' and 'mercy,' but there are likely to be difficult cases where we just aren't sure whether one or the other is being instantiated. But it doesn't provide us anything like a sure-fire means from which we can deduce that the bible is the word of God. At any rate, I'd like to see how Gangadean defends his notions of divine justice and mercy from any and all possible contenders.

Beyond that, there's an additional worry about how these twin notions work together. For Gangadean, the bible provides the only account of the reconciliation of divine justice and mercy in the face of sin. There is no other current competitor to our knowledge [notice: he has no epistemological right to say that there is no possible contender].

So in his mind, if we have reasoned carefully and correctly from basic things, we'll all "see" that there is some puzzle to be solved. We'll know with certainty that there is such a thing as sin, that humans have all sinned and also that God is infinitely just (as Gangadean defines it) and infinitely merciful (as Ganagdean defines it). And crucially, we'll further see a real tension between these. The tension is this: if God's justice demands payment for sin, and all have sinned then this is supposed to present some obvious puzzle for God's mercy. But to be frank, I don't know what that puzzle is. As I stated above, I've yet to hear Gangadean's theory of infinite mercy and so I can't even begin to assess whether or not there is some tension with his notion of divine justice. Without this tension, there's no need for special revelation and no "deduction" to the bible as the word of God.

Now, if we think about mercy in the legal setting we might think of it in terms of giving someone less than they deserve or else granting them favor (some good) that they don't deserve. But what would infinite mercy look like? Would it be to grant to all creatures who are undeserving, a little bit of favor? Or would it be to grant 49% of the undeserving, a bit more favor? Or perhaps only a handful with a whole lotta favor? Maybe just one person must get infinite favor? Or perhaps all undeserving creatures, less than infinite favor. Or perhaps all undeserving, infinite favor? How can we settle this via reason alone? I haven't a clue and neither does Gangadean.

What's emerging then is my puzzlement over Gangadean's purported puzzle. Gangadean can't define 'infinite mercy' in a way that contradicts his notion of infinite justice. Otherwise, God couldn't have both attributes on pain of inconsistency. But neither can Gangadean define 'infinite mercy' in a way that presents no tension with his concept of infinite justice or else by his lights, we could not come to affirm "the need for special revelation". Gangadean needs for there to be just the right sort of tension between the notion of divine justice and the notion of divine mercy that he purports to derive from reason alone. But just what is this notion of infinite mercy that he's got in mind? And what is his rational justification for adopting it in the first place? Your guess is as good as mine.

There are various theories of justice and likewise various theories of infinite/divine justice. Many Christians take themselves to have a rather strong grasp of divine justice since they often cite it to answer objections about the doctrine of eternal damnation, and the need for atonement. Gangadeanians are no exception. They believe that divine justice requires that sin not be set aside, but rather must be accounted for. For God to simply overlook or forgive wrongdoing would be to violate his nature as divinely just. So sin must have consequences.

As Gangadeanians see it, the wages of sin are spiritual death which is failing to know what is clear. This is because at root sin is the failure to seek to know what is clear (to live contrary to what it means to be a rational animal/human). Failure to seek leads to ignorance. It's not clear what the nature of the connection is-- but they claim that there is an intrinsic link between failing to seek and failing to know what is clear. I'm skeptical of this purported conceptual connection because it isn't obvious to me that it is logically impossible for a human to know without seeking. I wouldn't limit God to that extent--if God so pleased, it seems to me that it's at least logically possible for him to give a human knowledge directly.

So ignorance of basic things = the wages of sin for the Gangadeanians. It's a very cognitive notion.

But they also believe that God is also infinitely merciful. Gangadeanians believe that even though God cannot (i.e., it's a logical impossibility) merely overlook sin because on their view, this would be incompatible with God's divine justice, God is also merciful. So he must save some (more on this below). But what does it mean to save some? Well, it requires that God forgive some of their sins. It isn't that God ignores the sin, but God atones for it or else again his divine justice would be threatened.